There are countless good reasons why anyone connected with Indian culture would do well to know at least something about the rise of the Shramanas shortly before the time of Lord Buddha (c.a. 700 BC) and the thus initiated so-called “Hindu synthesis.”

In short, the Hindu synthesis is the most defining synthesis of the spiritual and cultural heritage of two of the most prominent Indian communities – the Brahmanas and the Shramanas. This synthesis has massively shaped and changed the face of Indian culture, and it still continues today in an ethos of freedom to reform. In the face of such importance, it is highly astonishing how little people know about the Shramanas – what to speak of the Hindu synthesis. There is also very little sources of knowledge available on this topic and thus one has to do research and collect content from various books and other media. This article hopefully helps in getting a foothold in this topic. It is aimed at progressive people who are at least a bit conversant with Indian culture.

Vyasadeva, the saint who divided the single Veda into four and is believed to have composed the Mahabharata and Bhagavata Purana.

Probably it is not just a coincidence that I am completing this article shortly ahead of Guru Purnima, one of the biggest Hindu festivals and holidays, on which the sage Vyasadeva’s appearance day is celebrated. On Guru Purnima, also all Gurus are honoured, as Vyasadeva is venerated as being the embodiment of all Gurus. Perhaps lesser known, Vyasadeva is also one of the biggest reformers of Sanatana-dharma or Hindu faith. The Bhagavata Purana or Shrimad-Bhagavatam is one of the most-read holy scriptures of Hinduism. For millions of Hindus, it is considered the most sacred book. As mentioned in the beginning of the Bhagavata Purana, before compiling this book, Vyasadeva was in a spiritual crisis. His Guru Narada Muni explained to him that his dissatisfaction came from failing to highlight the worship of the Supreme Personality of Godhead in his earlier works and thus instructed him to compile the Bhagavata Purana, after doing which Vyasadeva was finally fully satisfied.

It is important to note that Vyasadeva didn’t present this scripture as a continuation of his earlier works, namely the division of the Vedas and the compiling of the Mahabharata, but as a reformatory scripture that openly rejects the ethos advocated in his earlier works as cheating religion (dharmaḥ projjhita-kaitavo, Bhagavata Purana 1.1.2). In contrast to the wide-spread belief that Guru and the scriptures are infallible, Vyasadeva himself was not shy to proclaim by his very own example that they are both not infallible. Unlike many pseudo-gurus of today who try to hide and white-wash their mistakes and the shortcomings of other spiritual authorities, Vyasadeva had the spiritual strength and courage to lay in front of the people his own erring as well as his own self-correction in the form of the Bhagavata Purana. How much tragedy and hyprocrisy could be avoided if today’s spiritual leaders would not just claim to be Vyasadeva’s followers, but actually followed in his footsteps and were frank about the fallibility of the Gurus and scriptures (more on this topic here) and about the need of continuous correction and reform!

Did I say continuous correction and reform? I did. Although this may not sit well with overly orthodox-minded people, the reality of fallibility brings with itself the necessity and duty of constant re-assessment and reform, just as software needs to constantly be updated. Some people may say that the Bhagavata Purana was the last update needed – ever. But that would not only be impractical like avoiding software updates; it would directly contradict its author, Vyasadeva, who gave the example of self-reform both boldly and publicly. Why is reform needed again? Because of fallibility and changes in the environment. The only event that could scrap the need of continuous reform would be if all leaders would suddenly become infallible and if the environment stopped changing. And I think we all agree that this will most likely never happen. If anyone needs another proof of how the spirit of continuous reform is already imbedded in the ethos of Indian thought, we already have it in the wide acceptance of the Bhagavata Purana. If the people were strictly against any substantial reform at the time of its publication, the Bhagavata Purana would have been rejected from its onset. The acceptance of the Bhagavata Purana as a holy scripture stands as proof of how progressive and appreciative of reform the people were during its appearance.

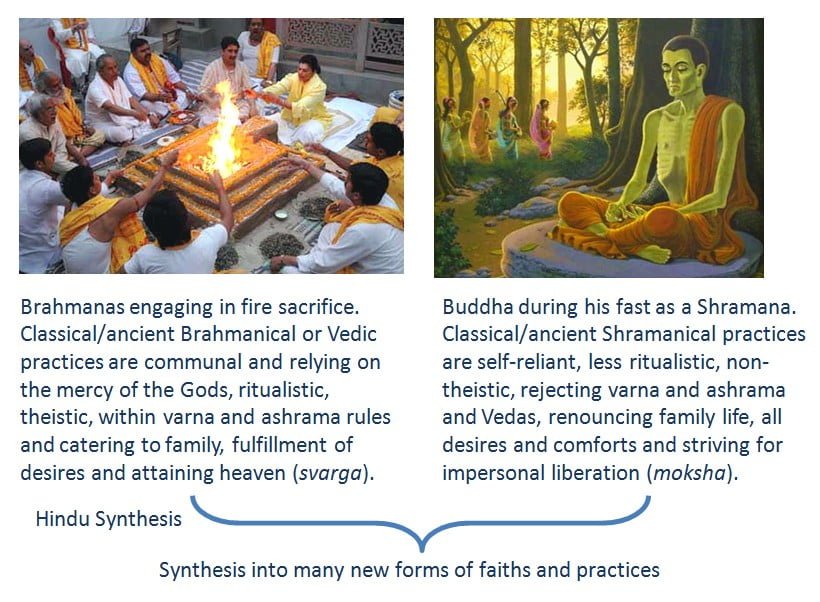

To begin this article, I wanted to highlight this important Indian ethos of continuous reform. This ethos was not only exemplified by Vyasadeva and many other Hindu saints, but it is also embodied by the entire collective of evolution of Hindu culture. Like every other culture, the Hindu culture has been in a constant flow of reassessment, synthesis and reform. The biggest of all such syntheses is the so-called “Hindu synthesis,” which we shall discuss more in this article. This synthesis is the biggest embodiment of reform in Hindu culture, and it continues till date. As already mentioned, and as illustrated in below diagram, the Hindu synthesis is the synthesis of the spiritual and cultural values of two of the biggest Indian spiritual communities – the Brahmanas and the Shramanas.

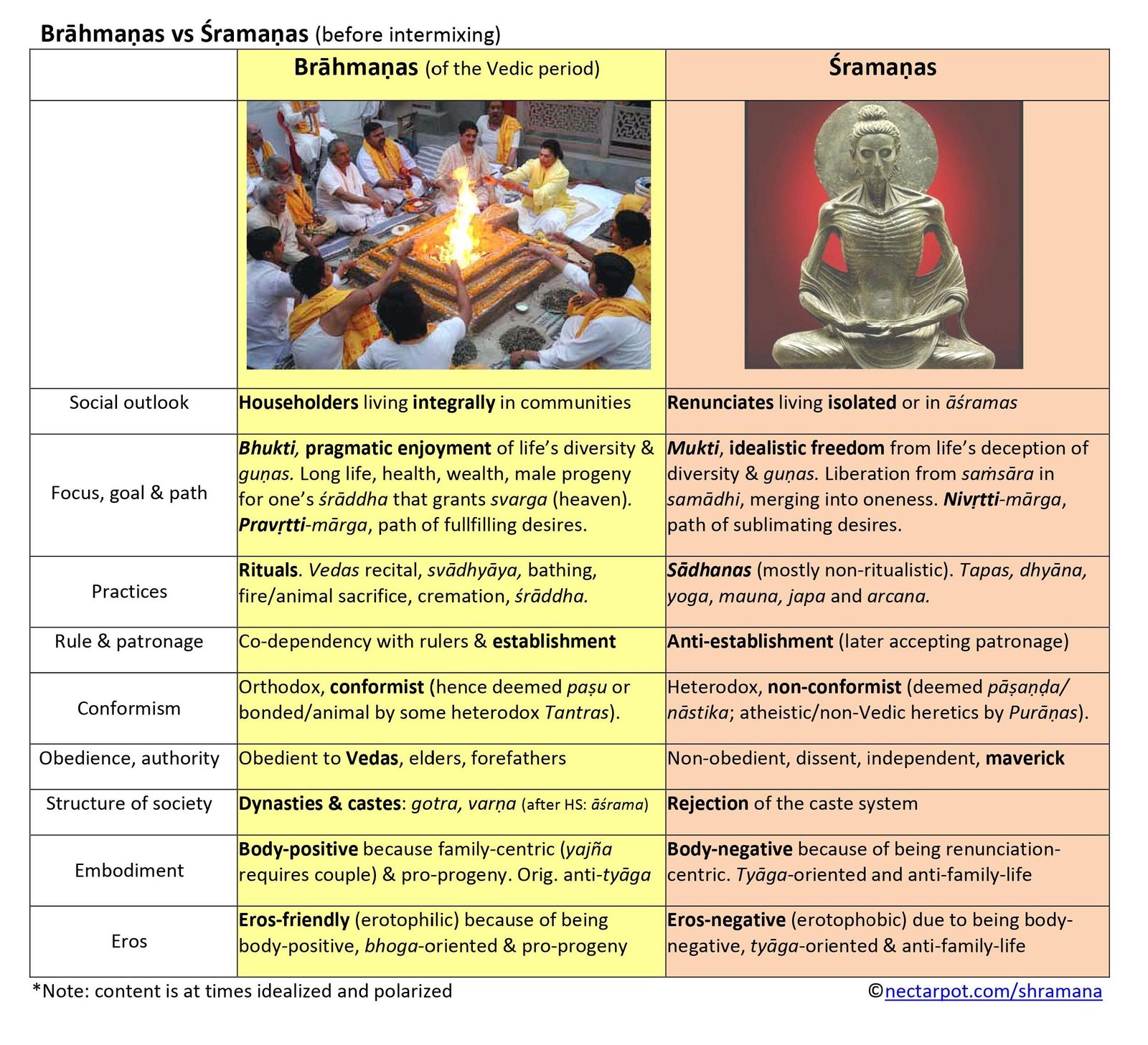

People in general know more about the Brahmanas and little to nothing about the Shramanas. Although everyone knows Buddhism, Yoga and Tantra, only few know that they were all founded in the ethos of the Shramana community. A Śramaṇa (Sanskrit: श्रमण) is one who labours or exerts him- or herself for some higher spiritual purpose (the verbal root śram means exertive striving). While the orthodox Vedic Brahmanas traditionally were society-centric householders engaged in uplifting Vedic rituals that were often reserved for the higher castes, the heterodox or unorthodox Shramanas rose in opposition to the caste system and were mostly individuality-centric renunciates.

Below table gives an overview of the most defining characteristics of both groups. You can download and view the more elaborate version of this table as a pdf here. Note that this table is at times polarized and that there are always exceptions to the most common characteristics. We are attempting to learn about the differences between the Brahmanas and Shramanas and to that end a polarized vision is helpful. Such a high polarization in deed occured during the beginning of the Hindu synthesis. The famous Sanskrit grammarian Patañjali, who lived during this time (200 BC), compared the tensions between the Shramanas and Brahmanas to those between the snake and the mongoose, who are arch-enemies. He used the compound śramaṇa-brāhmaṇam1 to express perpetual enmity, pretty much as nowadays in English people say “cats and dogs” to express the same. As you would expect from any synthesis, in the course of the Hindu synthesis, this strong polarization evolved into more friendly co-existence and further cultural cross-pollination between the Brahmanas and Shramanas.

The Shramanas originally were spiritual seekers who avoided organization. However, many well-organized Shramanic traditions soon evolved from them, the most well-known ones being Buddhism, Jainism, Yoga, and Tantra. The most famous story involving Shramanism is that of Lord Buddha who, before establishing his own path, was a Hindu prince who left his Vedic community and joined the fold of the Shramanas (“Samanas” in the Pali language, in which many Buddhist texts have been written).

The Shramanas originally were spiritual seekers who avoided organization. However, many well-organized Shramanic traditions soon evolved from them, the most well-known ones being Buddhism, Jainism, Yoga, and Tantra. The most famous story involving Shramanism is that of Lord Buddha who, before establishing his own path, was a Hindu prince who left his Vedic community and joined the fold of the Shramanas (“Samanas” in the Pali language, in which many Buddhist texts have been written).

If we examine any of the present Indian traditions, we will find that they contain a particular mixture of Brahmanical (traditionally Vedic) and Shramanic values. This particular mixture, which is typical for all Hindu traditions, is the outcome of the Hindu synthesis, the synthesis of the Brahmanical and Shramanical traditions.

For example, let us look at the Bhakti traditions. Although many of their members call themselves “Vedic”, academia has often classified them as Shramanic, as their core beliefs are rather Shramanic than Vedic. They are mostly body-negative and renunciation-centric (most Bhakti role-models and leaders are renunciates, for example) and focus more on personal sadhanas granting higher stages of Bhakti (the Bhakti version of liberation) rather than Vedic rituals granting material upliftment and heaven.

Now, why does all this matter? It matters in many ways. Most remarkably, because many people don’t know how their tradition formed through the Hindu synthesis, they are not aware of how their tradition contains a mixture of values from various traditions, mainly the Brahmanical and the Shramanical ones. Not knowing about the Hindu synthesis as someone who identifies with any Indian tradition comes down to not knowing the basics of one’s own history. It’s basically like being ignorant about one’s own parents and their history.

Many people for example wonder how it is possible that we find many relics of a very body-friendly and Eros-friendly culture all over India such as the Kama-sutras and the temples of Khajuraho when most Indian traditions today are even more body-negative and erotophobic than other world religions that are famous for being prudish. The answer to this question lies in understanding the dynamics of the Hindu synthesis.

Although it is often believed that Indian body-negativity roots in imported values of Muslim and Christian invaders, most of it actually originated on Indian soil when the Shramanas rose around 700 BC. The Shramanas who promised freedom from the caste system and spread ahimsa (freedom from cruelty, particularly rejecting Vedic animal sacrifices) were highly attractive to the people at the time and many thus didn’t mind paying the price of renunciation of family and body comforts to join their fold. The Vedic societies thus lost more and more of their sons to the Shramanas and in answer to that threat started to incorporate Shramanic values into their own core values, even the advocation of renunciation (the earlier Brahmanas were strongly against renunciation). The two-fold spreading of Shramanic values through the Shramanic traditions (Buddhism, Yoga, Tantra, etc.) as well as through the now newly “Shramanized” Vedic traditions lead to a massive shift from family-centrism to renunciation-centrism across India. This shift also brought within itself a shift to wide-spread body-negativity and erotophobia, from which most Indian traditions and people still haven’t recovered.

Hence, although today we still find relics of an earlier body-positive culture everywhere, these mostly only remain silent witnesses in the backdrop of the deeply ingrained body-negative culture of India. However, if anyone associated with Indian traditions wants to become more body-positive – and there is in fact a big trend towards that – they don’t have to look very far and try to reinvent the wheel. They can simply engage in reform and revert to the originally body-positive culture of India.

We can now similarly take any other value, ethos or philosophical concept of our current tradition and look at it through the lens of the Hindu synthesis. We will be surprised, how many of them such as the concepts of saṃsāra and mukti actually were Shramanic concepts that were incorporated during the Hindu synthesis and were not yet present in the Vedas. In order to understand this historical development, it is of course crucial to know at what time certain scriptures appeared. The graphic below gives an overview. The dating given here is that of the scholarly or scientific consideration, which can be found in scholarly media and also on common platforms like Wikipedia.

Another interesting excercise is to go through the characteristics of the earlier table (here) and see which elements of our tradition (and/or other traditions) came from Brahmanical and which came from Shramanical origins. The insights of the perspective of the Hindu synthesis can be eye-opening. I am not saying that either the Brahmanical or Shramanical traditions are better. Both traditions have unique values and have dealt with their shortcomings by evolving further during the Hindu synthesis.

In brief, the Brahmanical traditions have great family and community values but these tend to corrupt if monopolization creeps in. The Shramana traditions thus opposed such corruption and embodied their anti-thesis, but in doing so they went to the other extreme of proclaiming not just renunciation of family but even of all desires and of organized religion and even of God as a person as the right path. During the Hindu synthesis, a lot of renunciation spirit was thus incorporated into the flow of Indian thought, and while this synthesis is still continuing today, people are realizing that further synthesis is needed to further lessen the pressure of extreme renunciation and again become more family-friendly, body-friendly and Eros-friendly like most Indians were in the older days, while keeping away from shortcomings like monopolization that have truly proven to be harmful over time. And thus the synthesis continues and is inviting all of us to contribute to it as active and creative synthesizers.

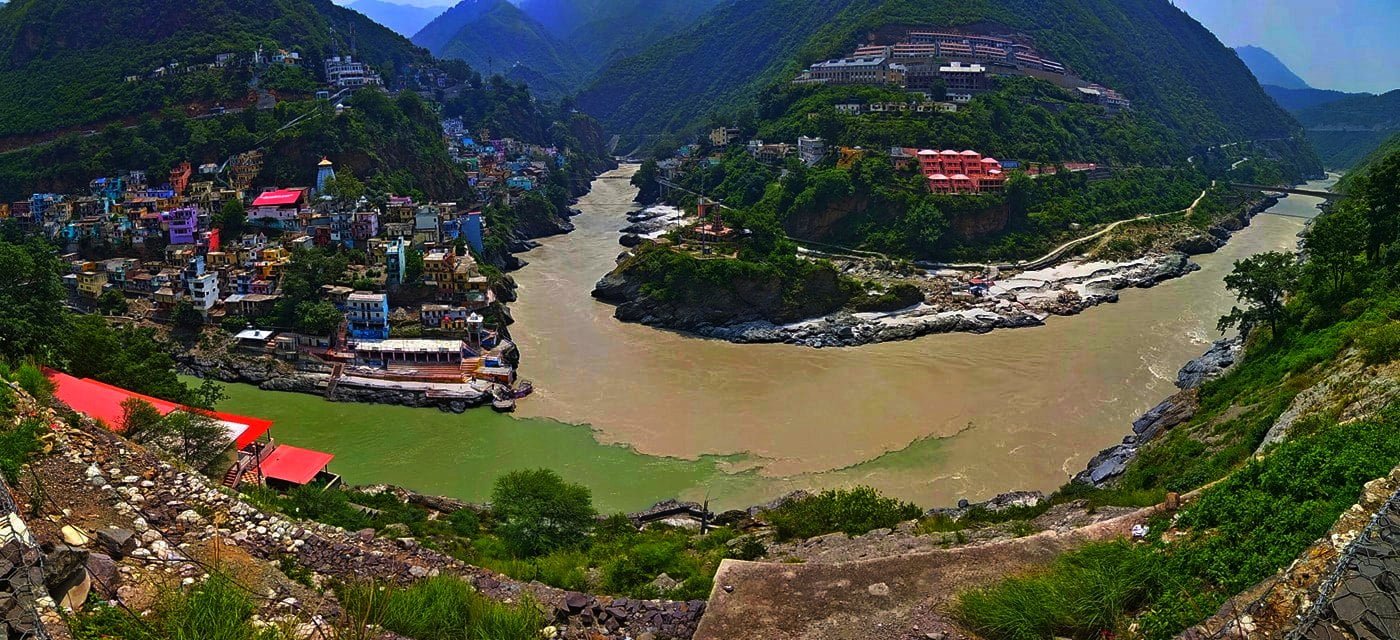

We are unique individuals, just as every spiritual tradition is unique. To flourish spiritually, we require and deserve a set of beliefs that matches our own individual nature. Many have already chosen a certain tradition to adhere to and this particular tradition has already undergone a certain path in the Hindu synthesis. It can be compared to the Ganga river that has assimilated various different waters along its paths from countless different sources. In below photograph and video we see the famous merging of the Bhagirati river (coming from Gangotri with its greenish waters) and the Alakananda river (coming from Badrinath with its brownish waters) forming the Ganga river in Devprayag:

River confluence in Devprayag. PC: Radhamadhav Das

When we think of the Ganga river we ususally think of it as containing a single type of water, but in reality it carries a variety of waters from different sources. Similarly, we usually think of our tradition as an unmixed body of knowledge, but in reality it is a mixture of knowledge and practices from countless sources. We could picture the Bhagirathi and Alakananda rivers merging into Ganga as the Brahmana and Shramana traditions synthesizing to evolve into the contemporary Indian traditions to give us some idea of Indian history of religion.

In reality, it was of course much more complex, just as you have countless more contributors to the Ganga river than just the Bhagirathi and Alakananda rivers. When we become more aware of when and from where which elements came into our tradition, we start to get to know our history better, and with it, our multi-facetted roots and identity. We can then also realize that we don’t need to automatically accept each and every element of our tradition, but just as our tradition can be compared with a river that has the freedom to constantly keep meandering or reforming and changing its flow and mixture of water, we too have the freedom to compile our own mixture of values and practices according to our individual requirements and aspirations.

People may ask, if the form of the tradition keeps changing, can the tradition really claim to be embodying the spiritual substance, which is said to be eternally unchanging? In answer to this it can be said that just as a river may meander and thus keep on adjusting its external form to the changes of the environment but still always carry the same water, similarly, a tradition may make certain external adjustments according to the changes in the environment, but still stay true to the essence of its teachings, which always remain the same. Also, to claim that one’s tradition never changed would always come down to hypocrisy as there is not a single tradition of mankind that hasn’t changed substantially over time. So it is better to embrace the natural law of continuous external change openly and learn how to flow with it in the best way possible. Perhaps the strongest argument for perpetual adjustment is the fact that, although it appears very counterintuitive and paradox, the best way of conserving the essence is to make sure that its packaging always keeps on being updated and adjusted to changes in the environment, just as the best and most natural way a river serves its essence or water is by continuous adjustment, and not by way of forceful cementation of its embankments – in fact, if any river’s embankments would be cemented, it would cease to be a river and turn into a liveless canal!

God made us uniquely unique so God can relish our uniqueness, not to punish us with frustration over not being able to fully fit in anywhere. God wants to relish our unique being, and for that we have to allow it to flourish naturally. If some people try to tell us that we don’t have this freedom, the Hindu synthesis as a historic collective and as an eternal ethos of ever-new re-orientation, recollection, reform and synthesis answers them: “Yes, we very much do have this freedom!”

By Radhamadhav Das, a researcher and author living in Vrindavan, India.

Sources:

- ŚRAMAṆA VIS-À-VIS BRĀHMAṆA IN EARLY HISTORY. S. D. Laddu. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute,Vol. 72/73, No. 1/4, Amrtamahotsava (1917-1992) Volume (1991-1992), pp. 719-736 (18 pages). Published By: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

- Sramanas: Their Conflict with Brahmanical by Padmanabh S. Jaini in Joseph Elder (ed.), Chapters in Indian Civilization, 1970.

- The special meanings of śrama and other derivations of the root śram in the Veda. H. W. Bodewitz.

- Śramana tradition: its history and contribution to Indian culture. G. C. Pande. L. D. Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, 1978.